The term “selling” might seem blunt, but there’s no better word to describe the reality of K-pop today.

The thought that idols might be selling their emotions too crossed my mind after watching the recently released documentary about LE SSERAFIM. On July 29th, HYBE released a five-part documentary titled “Make It Look Easy”, which captures LE SSERAFIM’s journey from practicing for their end-of-year performance in 2022 to preparing for their third mini-album “EASY” in 2024. The documentary focuses on the efforts and pain the members endured behind their glamorous appearances.

LE SSERAFIM isn’t the first group to show the darker side of idol life. BTS and BLACKPINK have also released documentaries that revealed their struggles. Such documentaries have become a staple in idol content. However, LE SSERAFIM’s documentary stands out for its raw and detailed depiction of the members’ suffering.

In the first episode, member Eunchae experiences hyperventilation during a comeback showcase but pushes through to perform. Another member, Sakura, is shown anxiously practicing with an oxygen mask before their debut. Throughout the documentary, the members are seen struggling in ways that seem excessive, even for something labeled as “effort”.

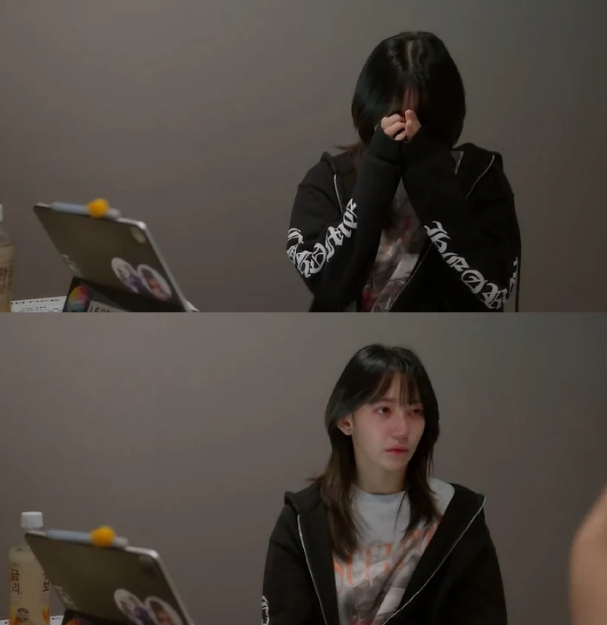

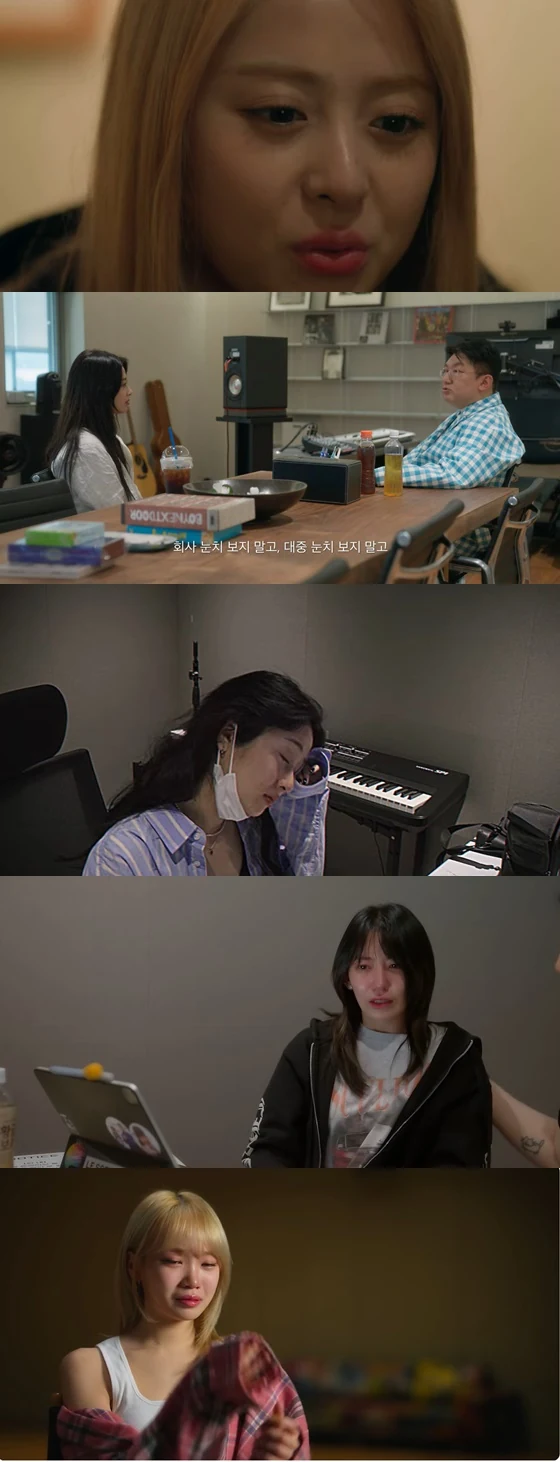

In the second episode, member Yunjin tears up during practice, saying she feels pressured by the public and industry insiders. In the third episode, Sakura suddenly bursts into tears and leaves the stage during a comeback show screening. The situation was so severe that even the filming crew had to stop. Reflecting on that time, she confessed, “I felt sorry to the fans because what I did well during practice didn’t work out (in real life), and I struggled because I had to keep smiling.”

In another episode, the members ponder, “Why did I choose to be an idol?”, “Is it worth it to keep doing this when it’s so hard?” and “I don’t know what will make me happy.” Except for the latter part of the final episode, most scenes show the members physically and mentally exhausted. One might wonder if their hardships were used as a dramatic element, given that LE SSERAFIM’s concept revolves around the idea of “moving forward without fear”.

While some viewers expressed support for LE SSERAFIM, others were concerned about the members’ mental health. Some criticized the documentary, accusing it of “emotional manipulation” or being staged for the sake of their concept. Edited clips of the members’ struggles have spread on social media and internet communities, leading to increased malicious comments directed at the members.

It’s unclear what exactly the documentary intended to achieve, but there must have been a “selling point” involved. But what exactly are idols selling, and how far are we willing to buy? In the K-pop market, terms like “sales” and “selling points” are often used. Like salespeople, idols must find their unique selling points to survive in the industry. This has led to a situation where idols must use even their hardships as a weapon to appeal to the public.

This phenomenon is fueled by the global expansion of K-pop and the constant debut of new idol groups, creating an environment where idols are easily replaceable. Idols are perfect “stars”, but at the same time, they have become “products” that can be replaced by other stars. While there’s always a behind-the-scenes aspect to their glamorous appearances, even that aspect has become commodified.

One glaring example of the commercialization of idols is “paid communication services”. For an average subscription fee of 3,500 to 4,500 won per month, fans can communicate with idols. The platform is designed to feel like a one-on-one chat, giving fans the impression that they are exchanging text messages with the idol. However, the service is highly capitalistic: multiple member subscriptions offer discounts, and shorter subscription periods limit the number of characters fans can send to the idol.

In the past, communication with idols was more about the “heart” than “money”. Fans would ask how idols were doing through fan cafes, leaving messages and comments at their convenience. But now, fans must pay to communicate with idols. This has subtly changed the relationship, turning idols into sellers of “conversation” and fans into buyers. The downside is a fandom culture that now prioritizes “value for money” over love.

When idols don’t log into the communication app frequently or send short messages, fans may complain that they aren’t “getting their money’s worth”. In one case, fans of an idol even started a hashtag campaign demanding refunds due to the idol’s lack of activity on the app.

When idols share their struggles or personal stories on the app, some fans offer comfort, while others respond by asking, “Do I have to pay to hear this?” Some even get upset when idols don’t reply to their messages. There have even been cases where fans skirt around the app’s banned words to send messages that border on sexual harassment. When controversies arise regarding the use of these apps, some fans defend the idols, “How often they log in is their choice” and “You can’t force communication.”

Since the advent of paid communication services, how kindly and frequently an idol sends messages or photos has become a new “selling point”. As fans flock to subscribe to what they call “communication hotspots”, idols have become emotional laborers selling fun to a faceless mass. One can’t help but think of the tearful faces of LE SSERAFIM’s members as they confess their struggles. As K-pop continues to expand globally, we must ask ourselves: Are the idols we love truly existing as people, or have they become mere dolls?